Concurrency Control in Ruby on Rails with PostgreSQL

Recently, I’ve been diving deep into database-related resources, and one topic that kept surfacing was concurrency control. Intrigued, I decided to explore it further.

By default, a Rails server starts with 5 threads to process multiple requests concurrently. When these simultaneous requests try to modify the same data in the database, anomalies can arise. Some well-known anomalies include dirty reads, unrepeatable reads, phantom reads, lost updates, and write skew—though other types are also possible. These anomalies can lead to data corruption, which is often hard to detect but can seriously compromise data integrity.

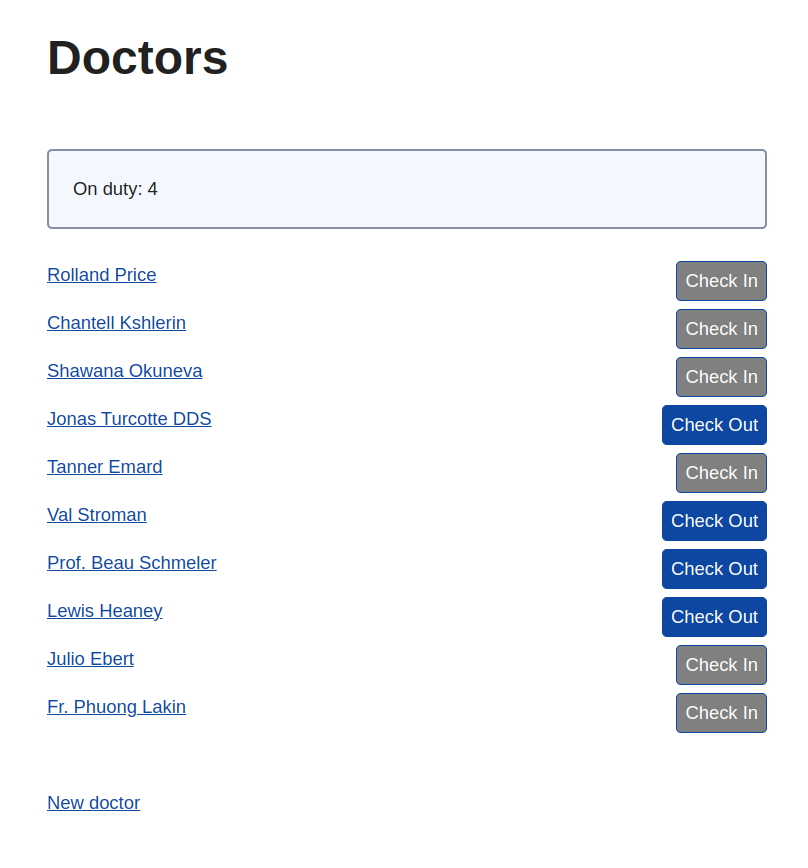

To better understand these anomalies, I created a demo application that demonstrates a classic write skew anomaly, inspired by the Serializable Snapshot Isolation in PostgreSQL paper. This Ruby on Rails app manages doctors on duty. It has a doctors table with a name (string) and an on_duty (boolean) field. For more details, check out the GitHub repository: https://github.com/SepsiLaszlo/doctors-on-duty.

The doctors can use the UI to check in and out of duty.

The system has one critical business rule: At least one doctor must be on duty at all times. To enforce this, I added a validation check that raises an error to prevent doctors from checking out if no doctors would remain on duty:

# app/models/doctor.rb

class Doctor < ApplicationRecord

MIN_DOCTORS_ON_DUTY = 1

scope :on_duty, -> { where(on_duty: true) }

def check_in!

update!(on_duty: true)

end

def check_out!

Doctor.transaction do

if Doctor.on_duty.count - 1 < MIN_DOCTORS_ON_DUTY

raise "At least #{MIN_DOCTORS_ON_DUTY} doctor(s) must be on duty"

end

update!(on_duty: false)

end

end

end

To simulate concurrent access, I wrote a Ruby test script. The script begins by checking in all doctors to set up the environment. It then enters a loop that continues until an anomaly is detected. To create an anomaly, the script launches 10 threads, each attempting to check out one doctor. After all threads have completed, the script verifies whether an anomaly has occurred. If so, the loop terminates; otherwise, it repeats.

require 'faraday'

count = 0

ids = (1..10)

while true

# Establish a consistent environment

Faraday.post("http://localhost:3000/doctors/check_in_all")

# Concurrently check out doctors

threads = ids.map do |id|

Thread.new do

Faraday.post("http://localhost:3000/doctors/#{id}/check_out")

end

end

# Wait for all threads to finish

threads.each(&:join)

# Fetch and display the number of doctors on duty

response = Faraday.get("http://localhost:3000/doctors/on_duty")

on_duty = response.body.to_i

puts "ITERATION: #{count += 1} ON_DUTY: #{on_duty}"

# Exit loop if an anomaly is detected

if on_duty == 0

puts 'ANOMALY'

break

end

end

After running the script, I observed the following output:

"ITERATION: 1 ON_DUTY: 1"

"ITERATION: 2 ON_DUTY: 1"

"ITERATION: 3 ON_DUTY: 1"

"ITERATION: 4 ON_DUTY: 1"

"ITERATION: 5 ON_DUTY: 1"

"ITERATION: 6 ON_DUTY: 0"

"ANOMALY"

The output indicates that, after the final iteration, no doctors remained on duty—leading to an inconsistent state. What caused this?

Imagine two transactions starting around the same time. Both check the system and see that checking out is safe because another doctor will remain on duty. They then check out simultaneously, resulting in both doctors leaving at once. Despite the safeguard, the transaction isolation isn’t strong enough to prevent the anomaly.

By default, PostgreSQL uses the Read Committed isolation level, which prevents dirty reads but allows non-repeatable reads, phantom reads, and serialization anomalies.

Increasing the isolation level to Repeatable Read or Snapshot Isolation (both of which use PostgreSQL’s internal snapshot isolation) would provide a stronger isolation, but these levels still allow serialization anomalies like the write skew, as described in PostgreSQL’s documentation for Transaction Isolation.

To eliminate all anomalies, we need to set the transaction isolation level to Serializable. This can be achieved by specifying the isolation level in the transaction method:

# app/models/doctor.rb

class Doctor < ApplicationRecord

# The rest of the code is the same

def check_out!

Doctor.transaction(isolation: :serializable) do

if Doctor.on_duty.count - 1 < MIN_DOCTORS_ON_DUTY

raise "At least #{MIN_DOCTORS_ON_DUTY} doctor(s) must be on duty"

end

update!(on_duty: false)

end

end

end

Setting the isolation level to serializable ensures that check-outs behave as if they are executed one at a time, preventing anomalies. However, PostgreSQL may need to abort some transactions to maintain serializability. In these cases, an ActiveRecord::SerializationFailure error is raised. We could either retry the failed check-out automatically or notify the user that his check-out failed.

Using the serializable isolation level does introduce some performance overhead since PostgreSQL requires additional resources to detect anomalies and retry aborted transactions. According to the Serializable Snapshot Isolation in PostgreSQL paper, using Serializable Snapshot Isolation can increase CPU usage by 10-20% compared to Snapshot Isolation.

Alternatively, locking could be used to guarantee serializability. Each transaction would need to acquire an exclusive read/write lock on the entire table to prevent anomalies. However, this would force transactions to wait for one another, negating the benefits of concurrent request processing.

It’s important to note that PostgreSQL only checks for serialization anomalies between serializable transactions. Therefore, all transactions must use the serializable isolation level to ensure no anomalies occur. Even ad hoc read-only queries run from the console could introduce inconsistencies if they don’t adhere to the serializable isolation level. Setting the database’s DEFAULT_TRANSACTION_ISOLATION to SERIALIZABLE could be a good precaution.

Summary

Concurrent execution enables web servers to process multiple requests simultaneously, but it also opens the door to anomalies. Databases can prevent these anomalies by using the serializable isolation level. However, some transactions may be aborted, and our application must be prepared to handle such failures gracefully.